Six months of sabbatical: between hustle and patience

Leaving Big Tech for creative self-employment

When I quit my corporate tech job, I had dreams of a free and expansive life as a self-employed creative. For context, I worked as a software engineer for 9+ years and started my art journey five years ago. Six months after quitting, I’m here to report that the reality of a self-employment/sabbatical hybrid has been a lot messier than I imagined.

What I’ve been up to

Whenever someone asks what I’ve been up to these days, my brain fails to grasp at anything concrete. It feels like I have been trying to do simultaneously everything and nothing. The question is not that deep; the asker merely wants a revealing tidbit that can spark further conversation.

When I pause to think about it, here is the highlight reel of what has filled my days:

Six months of vinyasa/ashtanga yoga teacher training along with a Buddhist studies program. I graduate this weekend!

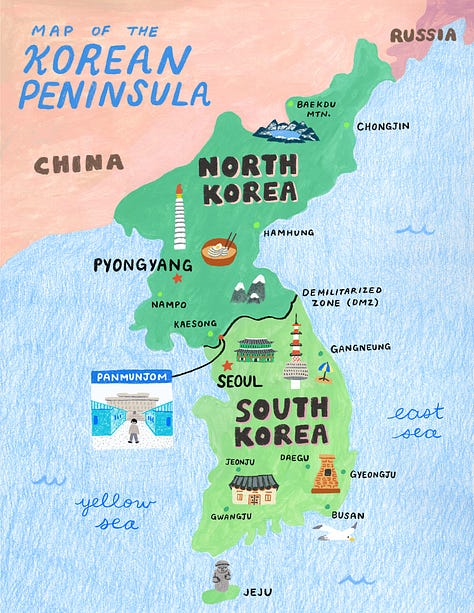

Traveling to Korea with family

Working on an illustration commission for a children’s magazine

Illustrations for Honest History Issue 27 Pouring more energy into this newsletter, ramping up paid subscriber offerings and seasonal themes (like January’s daily creative resilience challenge and spring’s zine challenge)

Making four new zines! I will properly share these soon… 😅

Taking a ten week risograph printing class at SVA’s RisoLab, getting way more familiar with the quirks of this wondrous printmaking technique

Mentoring creatives and engineers seeking clarity and guidance

Trying to go offline for a month and falling in love with stationery in the process

How I am doing

If the question “what have you been up to?” leaves me fumbling for words, then “how are you doing?” is a further kick down an existential spiral.

For the first two months after leaving my job, I was glowing. It felt so good to leave the corporate tech world behind, despite its high pay and cushy lifestyle. I no longer needed to operate in a hypervigilant state for on-call alerts or Slack notifications. I could stop being denied for promotion every cycle despite “doing a great job.”

The biggest relief from quitting was removing the cognitive dissonance of opposing generative AI as an artist while working for a company that centered its business goals around “done for you” AI technology. Despite missing engineering work and coworker camaraderie from time to time, I still am truly proud of making the choice to leave.

Once the glow wore off, unkind voices started to creep in. Am I wasting time? Am I doing enough? Am I doing the right thing? What is the right thing? What am I doing with this one wild and precious life?

It is a big privilege to be able to take a sabbatical. It is also a tricky choice to be made. Even amongst the privileged and able, self-led sabbaticals1 are not taken due to fear of the unknown. As the saying goes, better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.

I worked for many years and lived well below my means to be able to quit a job without knowing what’s next. As with all goals, once I reached this goal of taking a sabbatical, I was not forever satisfied and stress-free. Instead I stood face to face with a resounding Puritanic guilt that I must use this time productively to justify my existence.

If all I knew was work, perhaps work was the answer. Perhaps the right thing, the thing that people wanted for me, was to charge full steam ahead as a full time artist. My desire for a break from Big Tech was secondary to my bigger goal: the shiny dream of self-employment. Here’s what past me wrote upon leaving:

I would love to be able to generate enough self-employed income to cover my expenses, but recognize that this comes with lots of pressure and difficulty. If there comes a point where this pressure harms my practice and I can’t find a way out, then I am more than willing to get another full-time job.

To figure out whether self-employment worked for me, I first needed to try. So I put in the work. I worked on this newsletter. I ideated workshops and started teaching. I made new art products. I pitched myself to clients. All of these modes of earning are ones I’d tried while I still had my day job, but now I had more time and headspace to learn, create, and put myself out there.

Guess what? Trying is so embarrassing! Trying and failing has really tested my ability to love myself. So many days I feel tired of making mistakes, messing up prints and wasting tons of paper, forgetting about a Zoom call, or not setting up a proper email workflow.

When you’re an employee of a company, mistakes are just as emotionally fraught but you trust that there’s a team of people to help you out of the mess. When you’re flying solo or leading the ship, it’s on you to open up about your shortcomings and seek out support. For a sensitive, introverted artist, this is a hard pill to swallow.

In my efforts to seek connection, I went to see Timothy Goodman at a CreativeMornings lecture a few weeks ago. After showing his sizzle reel of many inspiring murals and artworks, he ended his talk with the quote below:

I shared this on Notes because I felt seen by Timothy’s acknowledgement that making a living as an artist is hard. I’ve since realized that this sentiment, while uplifting and validating, romanticizes the hustle culture that makes earning a living as an artist even more fraught today. The millennial heyday of 'doing what you love' was a philosophy born out of late stage capitalism, promising fulfillment and financial reward, but normalizing precarity and burnout in its stead.

I have lots of respect for Timothy and many other full time artists who have carved out their careers through this hustle. I grew my creative dreams looking toward these people. Even now I often wish I could work harder, promote myself more, and tune out my intuition telling me this isn’t the way. Maybe if I kept my head down and worked hard to the edge of burnout then chilled out later, I could ride the coattails of my prior success for the rest of my life.

But in a society that isn’t built for artists to thrive, hustling my way to self-employed success is an act of conformity that I continually resist upholding. I know I can’t sustain that life, so why would I use it as a shortcut?

What now?

The highlight reel at the start of this post might give the illusion that I've been hustling, but there is always more to be done. I could’ve been documenting my process on social media, or relaunched my website and shop. Like the choice of taking the sabbatical itself, it’s taken clear intention to not speed down the path of hustle. There may be more money and followers, but there is no peace for me there.

Instead I’m choosing to move slowly in building out my multifaceted small business. I am learning about anti-capitalist business and radical generosity through some of my favorite biz folks: Amelia Hruby, Sarah Faith Gottesdiener, and Nic Antoinette.

One of the best choices I made during this sabbatical has been to determine seasonal challenges for myself and for paid members of this newsletter. Making zines anchored my creative practice through the late winter and spring, and I’m really enjoying teaching others to make their own zines. Once the first iteration of Zine Lab ends, I will shift to my sketchbook practice and do more drawing outside, starting with some travel to Scotland in May.

If I had to identify the opposite of hustle, it would be patience. Despite my intention to move slowly, impatience is my default—a learned behavior from growing up with technology and modern conveniences, used to getting my way. My way of dealing with future uncertainty is to plan, so I’m trying to let go of planning and goal setting too, at least through the summer. If that means simply existing without much doing, then I hope I can learn to sit with it and still find love for myself.

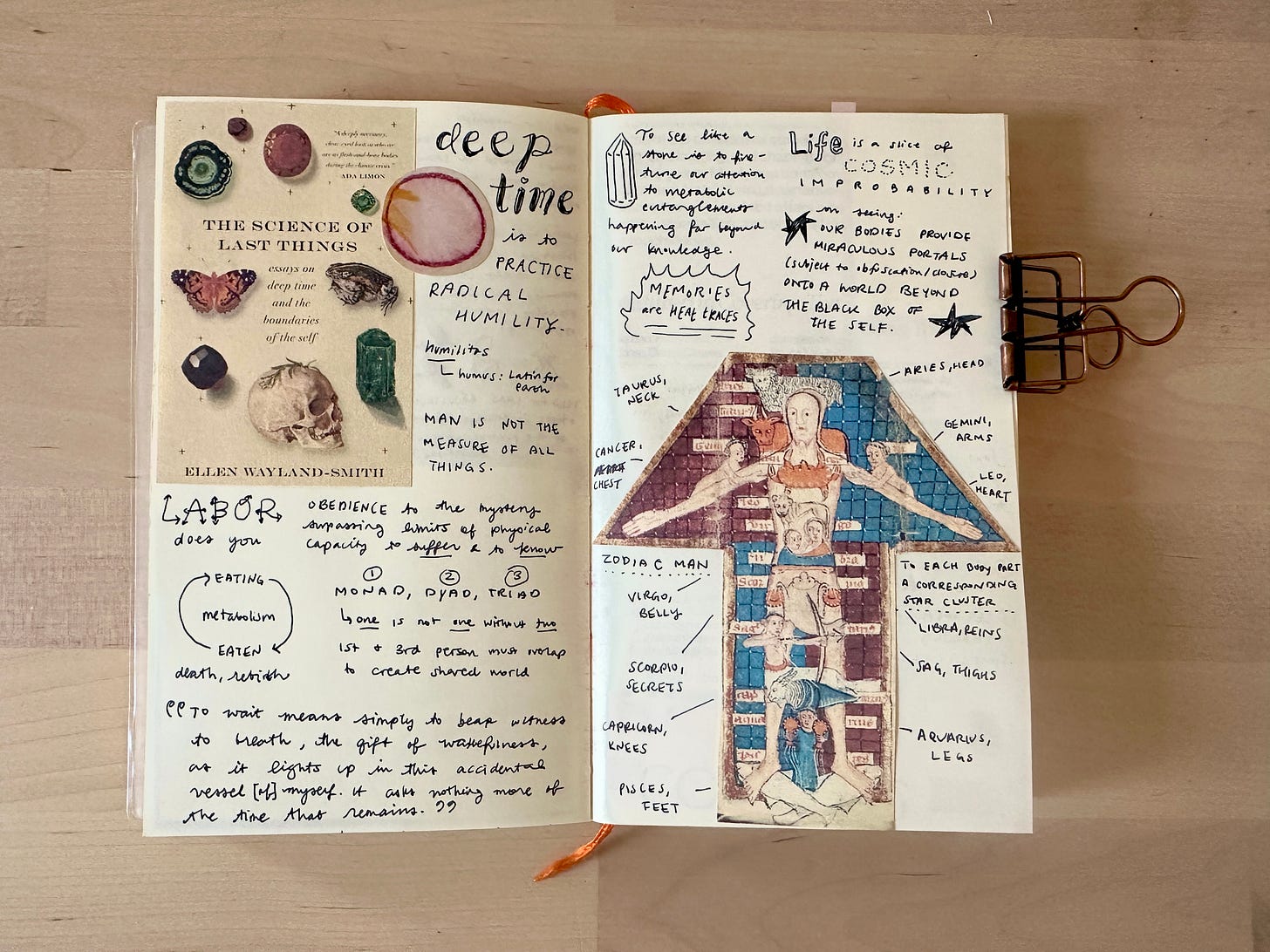

It helps to remind myself of the many jewels found in patience. Here is a passage that struck me from The Science of Last Things, a beautiful essay collection on deep time and the self by Ellen Wayland-Smith.

But there is a larger waiting, a cosmic waiting that precedes and cradles within itself all the other times and modes and tenses of being, like drops of water in an ocean. It tells us that our puny power to do and to be in this world is the exception, not the rule; that waiting is not the suspension of human business-as-usual, but rather the oldest and most elemental form of time.

Waiting is time itself. It is a gift to wait, to bear witness, to ask nothing of time while noticing all it contains.

☁️ If you have any stories or experiences to share about navigating the space between hustle and patience in your creative path, I’d love to hear from you via reply or comment! I’m still very much learning and evolving, so any wisdom or reflections you have are greatly appreciated, no matter where you are on your journey.

Also called “adult gap year”, or “mini-retirement” in this recent New York Times article

Carolyn, I look forward to discussing this with you more in-depth, but yes, it is SO hard. It's never ending hustle and that can lead to its own burnout that's different from corporate work burnout. It's hard to hold steady when your brain then starts to think that working a 9-5 and getting a paycheck and leaving work at the office is an easier route than the hustle of a small business. But what you've done in 6 months is impressive. If this is still your passion then the work is to shut down these internal voices of doubt. But know that you can always change your mind too. We've moved in and out of small business/full time job work for the last two decades whenever we needed to for financial reasons or because we were too tired of the hustle. Keep going though. It takes time to build a small business.

I'm right in front of the door of leaving the hustle behind. Monday is my last working day in the corporate world before I can label myself as pre-retired a..d my job will be offshored.

I am looking forward to more time, to slowness, to not 'having' to do anything.

Patience is not my thing either but lately I've learned that it can be replaced simply by a slower rhythm, less expectations and more contemplation.

I've learned that we're always doing the right thing, even if it feels like the wrong thing.